PART 1: BOOKER T. SPICELY

Source: U.S. Army

On the evening of Saturday, July 8, 1944, 34-year-old Army Private Booker T. Spicely climbed the steps of a local bus in Durham, North Carolina.

Duke Power (originally Durham Public Service) bus, circa 1942.

Source: Durham County Library

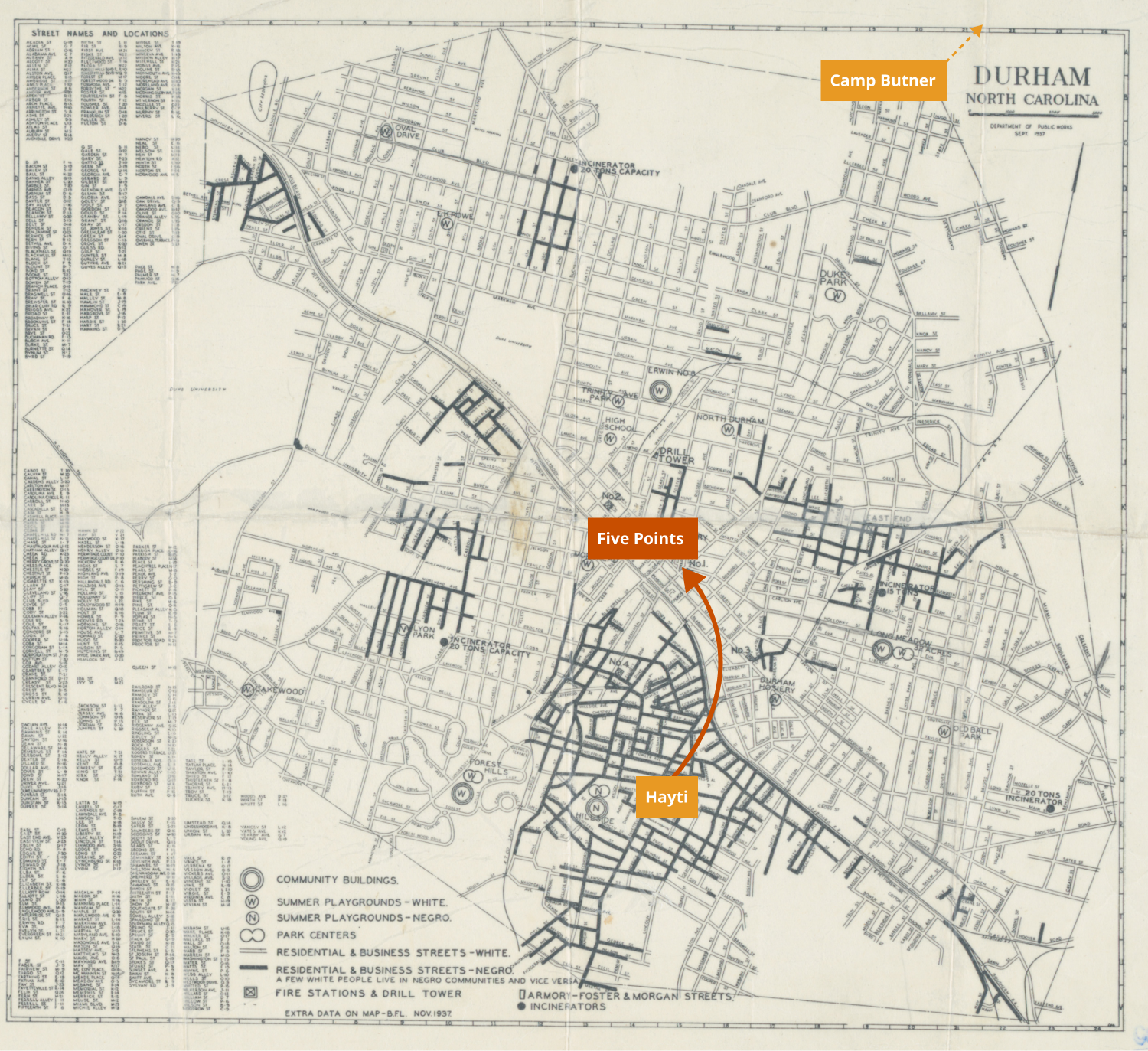

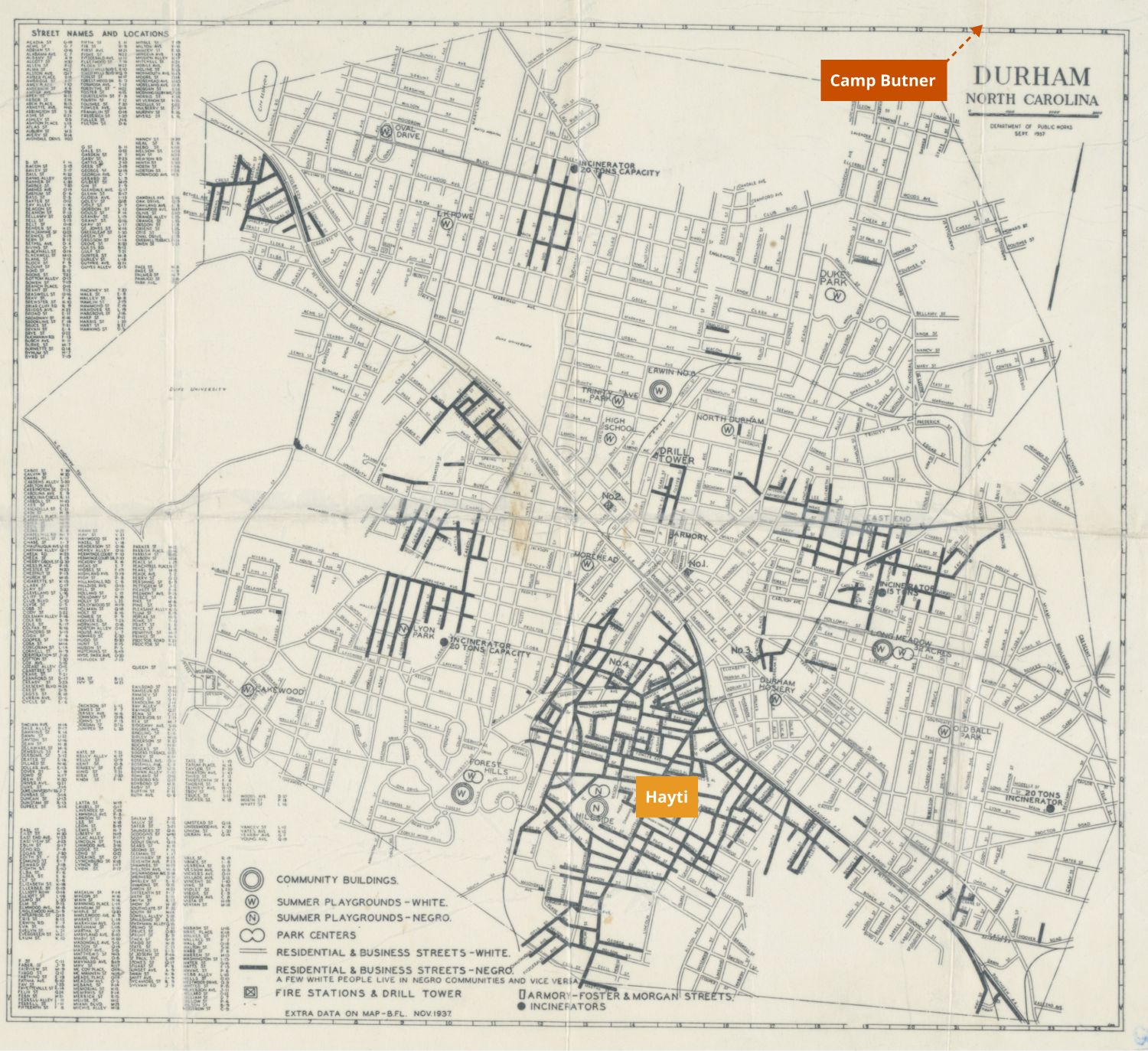

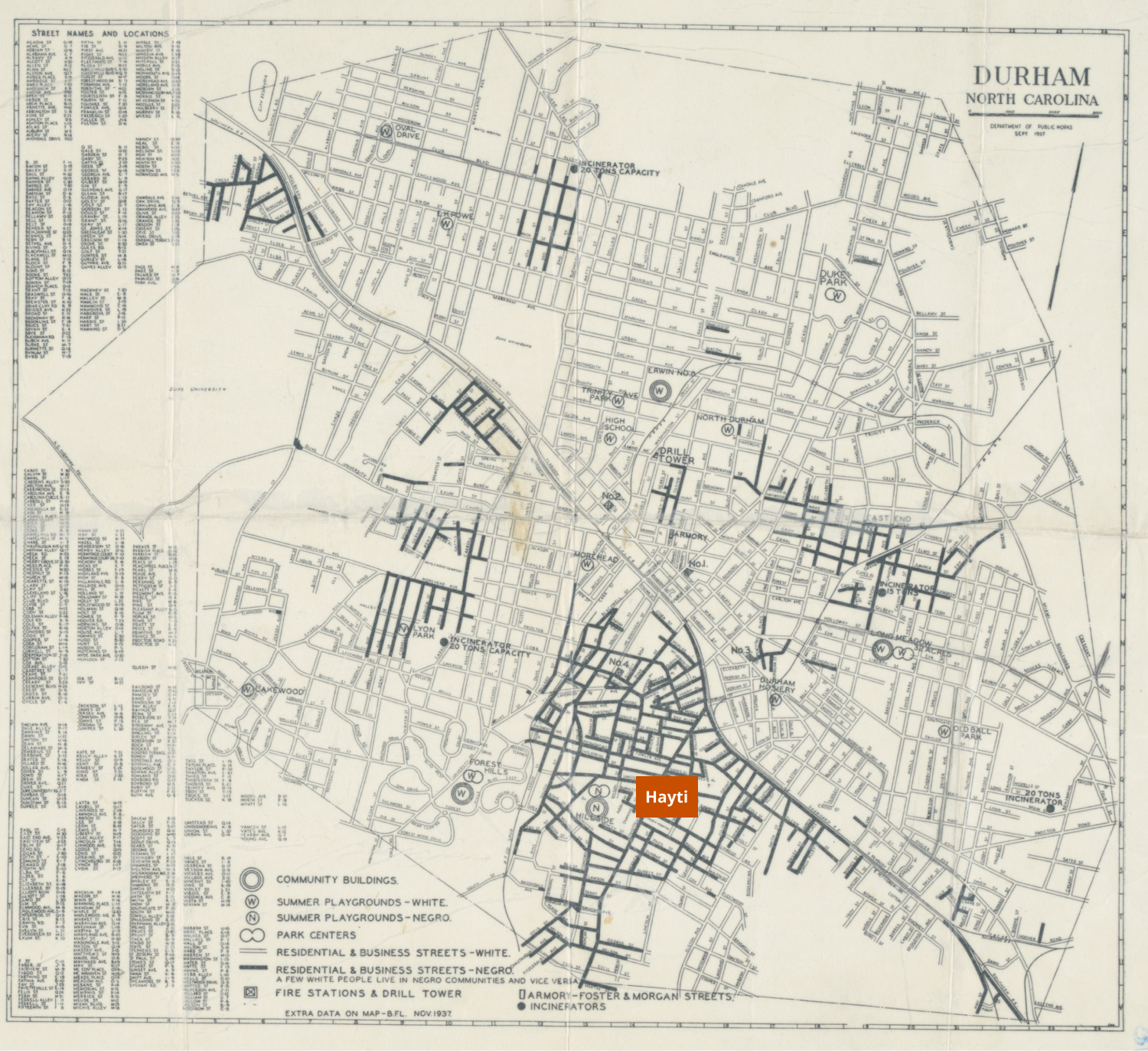

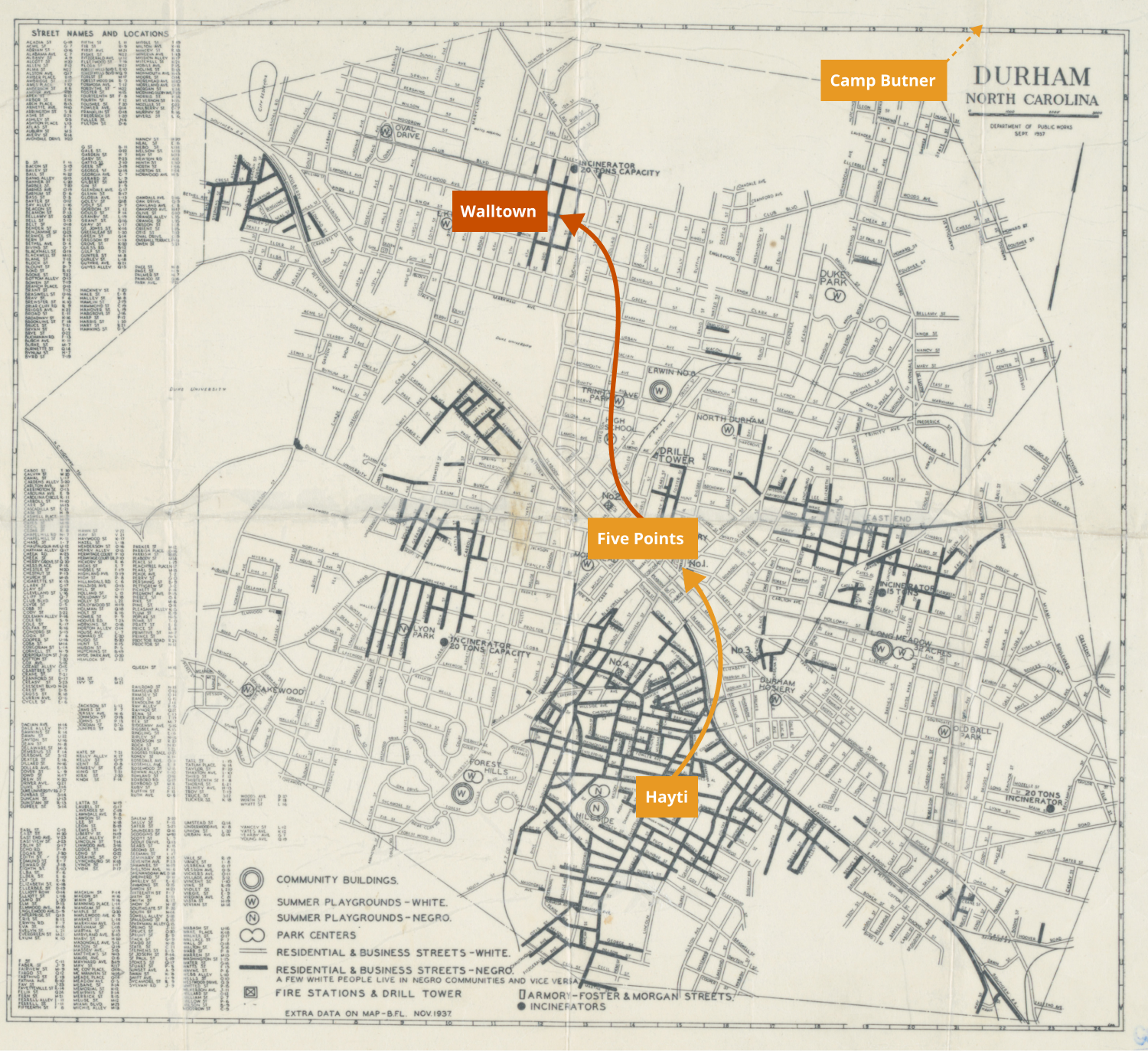

Spicely had spent his Saturday in the thriving African American neighborhood known as Hayti.

It was a place where Black soldiers came to relax and socialize after a long week of supporting the nation's fight in World War II.

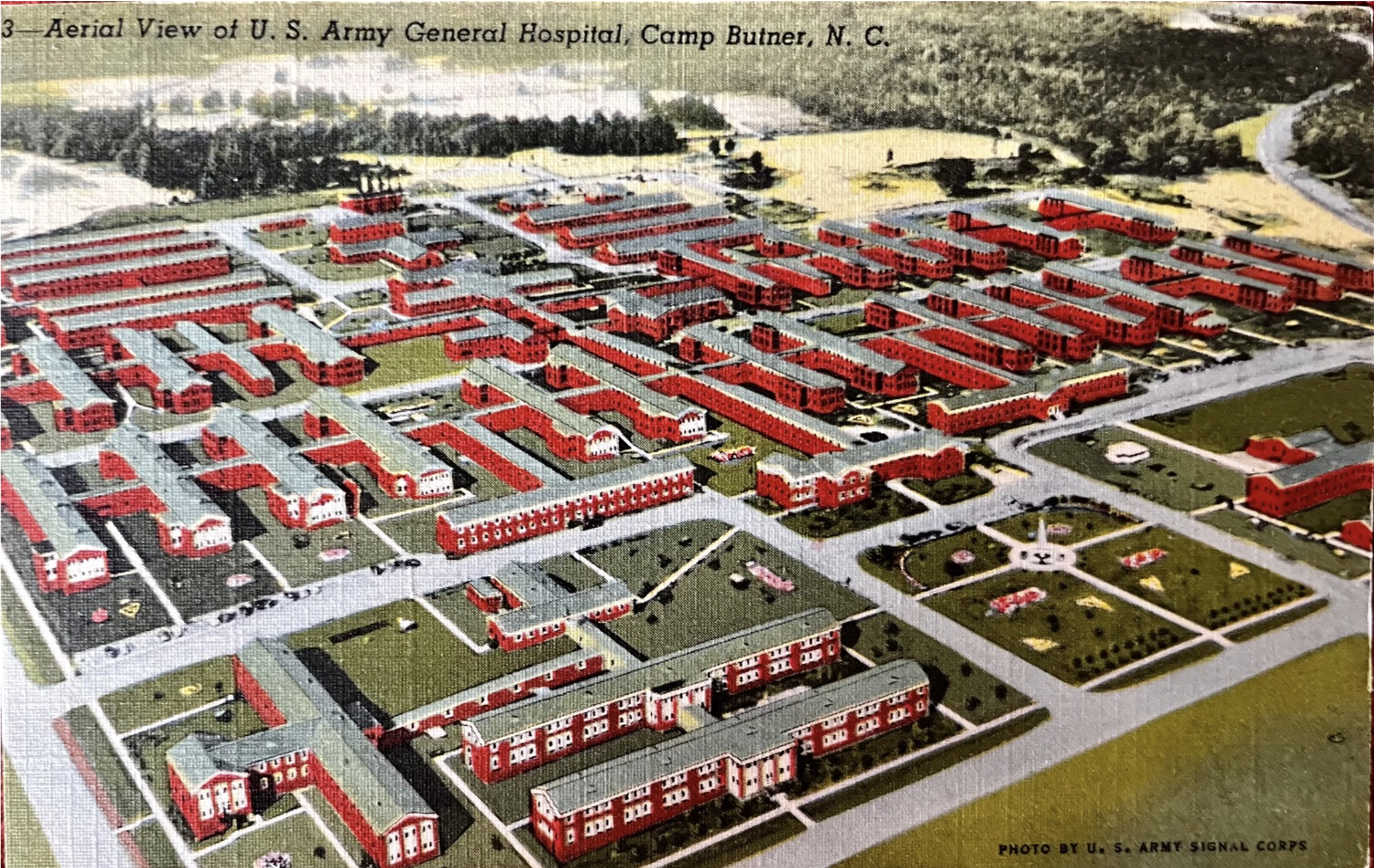

Then, the uniformed soldier boarded the bus back to Camp Butner – the large Army training base north of Durham where he served.

He never made it.

The bus soon stopped in the white neighborhood of Five Points to let more passengers aboard, including several white soldiers from Camp Butner.

The bus driver, a 36-year-old white man named Herman Lee Council, ordered Spicely and other Black passengers to move to the rear of the vehicle.

Spicely protested.

Source: Bangor Public Library

“I don’t see why I have to move back,” one white soldier recalled Spicely as saying. “I thought I was fighting a war for democracy, but it looks like it doesn’t work down here.”

Council and Spicely exchanged more words, witnesses said. Spicely obeyed the order.

When Spicely disembarked in the Black neighborhood of Walltown several stops later, Council followed him.

According to the bus driver’s testimony, Spicely’s right arm had reached toward his pocket, and Council feared he was carrying a gun.

Council fired two shots from the bus’s bottom step. One wedged in Spicely’s stomach; the other passed through his Army dog tag and lodged near his heart.

The uniformed soldier bled in the street. Council climbed into the driver’s seat and continued his bus route.

Military police took Spicely to nearby Watts Hospital, where doctors drew blood to perform an alcohol test. But they did not treat Spicely’s wounds: Watts Hospital served only white patients.

Booker T. Spicely died soon after reaching Duke Hospital, which reserved six beds for African Americans. He took his last breaths alone, far from his family in Pennsylvania and Virginia.

The alcohol test was negative. No weapon was found on the soldier.

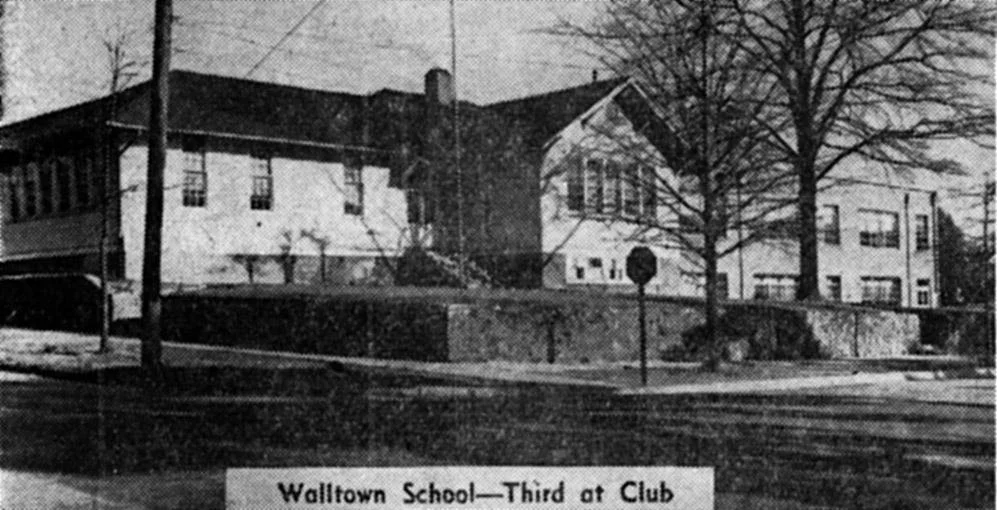

Image courtesy of John Schelp

Council finished his work day and turned himself in to local police.

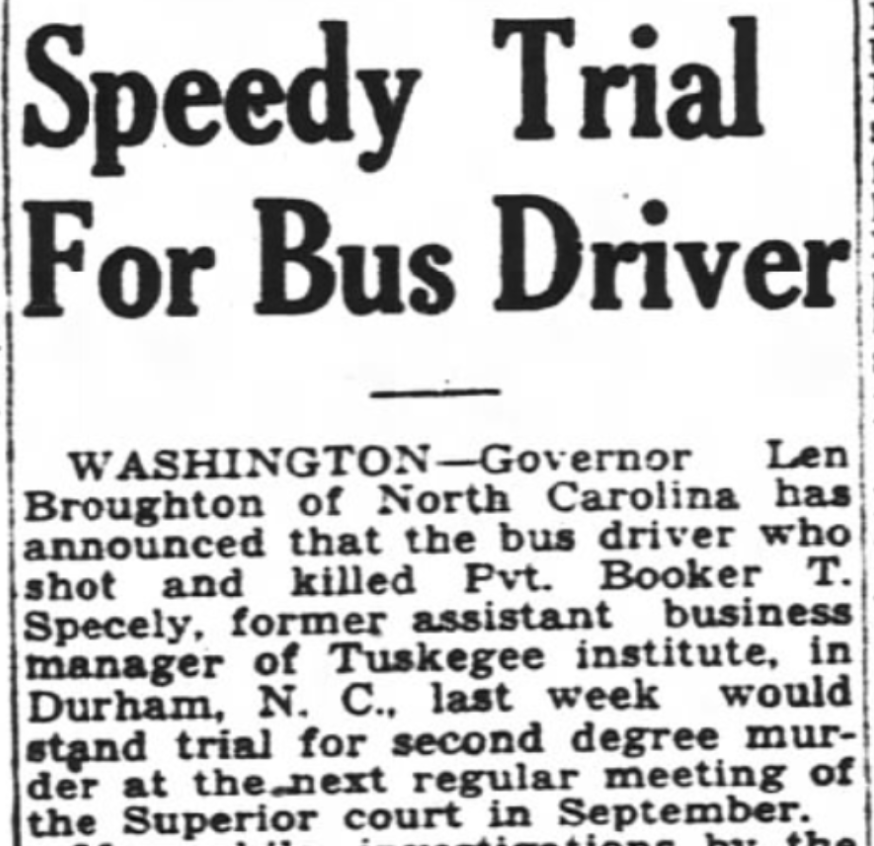

Council’s employer, Duke Power Company, operated Durham’s city buses. They posted the driver’s $2,500 bond and provided him with a lawyer. Council returned to his home until his trial for second degree murder in September of 1944.

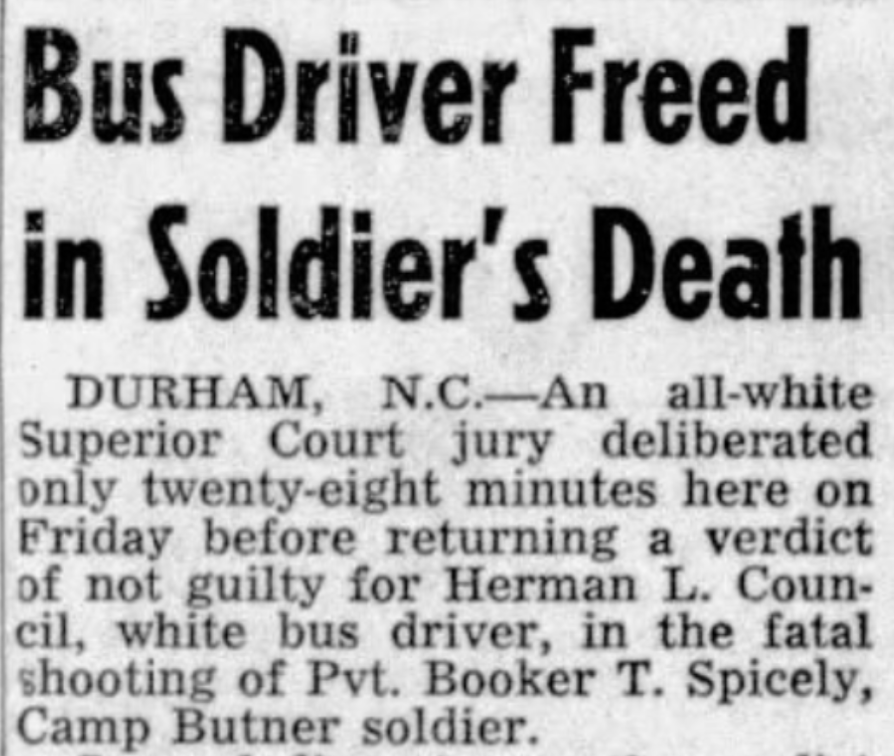

He was acquitted by an all-white jury after 28 minutes of deliberation.

Durham’s Black-owned and white-owned papers covered the shooting and trial in detail.

Durham Morning Herald

July 9, 1944

Durham Morning Herald

September 13, 1944

Durham Morning Herald

September 14, 1944

Durham Morning Herald

September 15, 1944

The Durham Sun

September 16, 1944

Durham Morning Herald

September 25, 1944

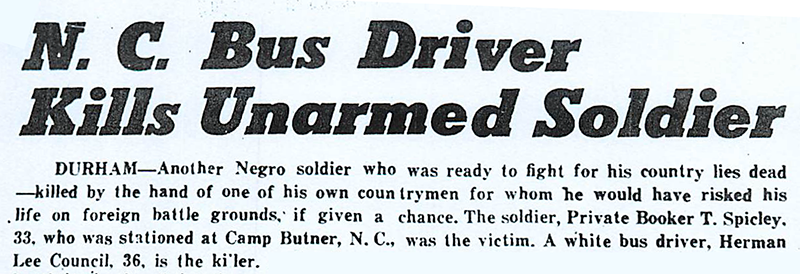

So did prominent Black-owned newspapers throughout America.

The Pittsburgh Courier

July 22, 1944

The People’s Voice (New York)

The Afro-American (Baltimore)

September 23, 1944

In the near future, you’ll view a performance of Changing Same: The Cold-Blooded Murder of Booker T. Spicely. This play was written in 2024 by Mike Wiley and Howard Craft, two North Carolina-based playwrights. It is a one-person show starring Wiley, who plays all of the characters.

Photograph by Jennifer Sanderson

Before viewing the performance, explore this website to learn more about Camp Butner, Durham, and America in 1944 – the year of Spicely’s death.

As you do so, consider these questions:

Why might Spicely’s death have been covered by newspapers in Durham and far from Durham – in Chicago, Baltimore, New York, and Pittsburgh? Why was Spicely’s killing national news?

What can Spicely’s life and death teach us about America’s relationship with the ideals of freedom and democracy?

Spicely story adapted from Margaret Burnham’s research, as presented in her 2022 book, By Hands Now Known.

Images courtesy of Duke University (map), Durham County Library (Hayti), John Schelp (Camp Butner, Five Points), and the (Durham) Herald-Sun via Preservation Durham (Walltown).